If I could change one thing about C++

30 Dec 2020 - John Z. Li

Before C++11, for a value type T,

there are only three possibilities with respect to

the parameter type of a function with respect to T, that is,

with a function named “f”, f(T), f(T&), and f(const T&).

The first one of them was inherited from C,

and the last two were due to C++’s own features.

When rvalue reference was introduced in C++11,

things became a little bit complicated.

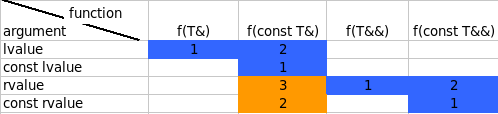

Below is a summary of binding rules with respect to

value categories and constness of arguments,

where a smaller number means higher precedence during overloading resolution.

The first thing one might notice is that f(const T&)

is special, for both lvalue and rvalue objects,

regardless of their constness, can bind to it.

It has to work this way, because copy constructors need this rule to work properly

in the pre-C++11 era.

After rvalue reference was added into the language,

it becomes a little bit uglier,

sometimes leading to unintended behavior.

For example, the following code actually invokes std::vector::push_back(const T&),

and the object is copied, though it seems like that the object is moved.

const T obj;

std::vector<T> v;

v.push_back(std::move(obj)); //this code actually copied the object.

Another example is that pre-C++11 code that is written following the Rule of Three. The C++11 compliant compiler will interpret a class with user-defined copy constructor and copy assignment operator as copy-only, implicitly deleting move constructor and move assignment operator for that class. This means performance penalty due to object of that type are always copied.

One observation is that if we can ignore the part marked by orange color,

the rules for arguments of lvalue reference will be perfectly

symmetric with the that of rvalue reference.

Symmetry is good, because symmetry means regularity, which in turns means easy-to-understand and hard-to-use-incorrectly rules.

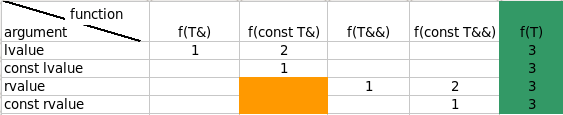

If we could just remove the orange-marked part and adding something else (explained below), we get the following:

Besides the orange-marked part being removed,

we also added another column for f(T),

which has lowest precedence in overloading resolution.

The current language standard says that if you have both f(T) and one of f(T&), f(const T&), f(T&&) or f(const T&&),

a call to f(-) is ambiguous.

The rationale behind my proposal is that while writing code, one can simply start with something like

class T{

public:

void fun(T t){} //handle both lvalues and rvalues

};

The method fun takes arguments of both

lvalue and rvalue,

regardless of its constness.

The programmer does not have to think about ownership issues at this stage,

object being copied around as needed,

so that he can quickly plow through the prototyping process.

If it turns out that passing by value has some problems,

like sub-optimal performance, binary bloat, or exceptions being thrown at the call site,

the programmer can add a overloading void fun(const T&), resulting something like the following:

class T{

public:

void fun(T t){} //handle rvalues

void fun(const T&){}; //handle lvalues

};

Now if argument passed in is an lvalue, fun(const T&)

will be chosen. The object can be copied inside the method body if needed,

and if the copy constructor might throw,

the exception can be caught and handled inside the function instead of at all call sites.

If the object passed in does not need to be copied,

performance can be improved because of less copying.

If the argument passed in is a rvalue, it will be moved and fun(T t)

will be called. If it is called like

T t;

t.fun(an expression that evaluated to a rvalue of type T);

the move will be eliminated because of optimization (copy elision).

This is almost equivalent with having both fun(const T&) and fun(T&&),

but should have the potential to also solve the annoying problem as given in

the first example.

If this is the case, the std::vector

can have the following two overloaded member function of push_back, that is

void push_back (value_type val);

void push_back (const value_type& val);

The compiler should be smart enough to figure out that

the following code intends to move the object,

(Note that from the perspective of the caller, fun(T) is equivalent with fun(const T),

and they have the same signature) but behaves like the object is copied into the function body:

const T obj;

std::vector<T> v;

v.push_back(std::move(obj)); //call push_back(value_type val)

rvalue reference can thus be saved for more esoteric cases, like perfect forwarding, or when the move constructor of the object can throw (throwing move constructors are rare though). In those rare cases, one can always add another overloaded member function with the signature

void fun(T&&); //if the move constructor of T can throw and

//you want to handle it inside the function.